October Optimism: Monthly Missives from The Dream Pedlar

Contemplating community and connection, in fiction and in reality

The big news this month that I must tell you right away is that I've been invited to speak on self-publishing at the Burlington Public Library's literary festival next month.

This is the first time (I think) I'm presenting my thoughts and insights to an audience as an indie author! After all these years of listening to many stalwarts speak and learning from them, it feels amazing to be able to do my bit in helping others along on their own journeys.

So if you're in or around Burlington and have the time, mark the date!

Let me know if you're planning to come, because I'd absolutely, absolutely love to see you and spend some time with you in person!

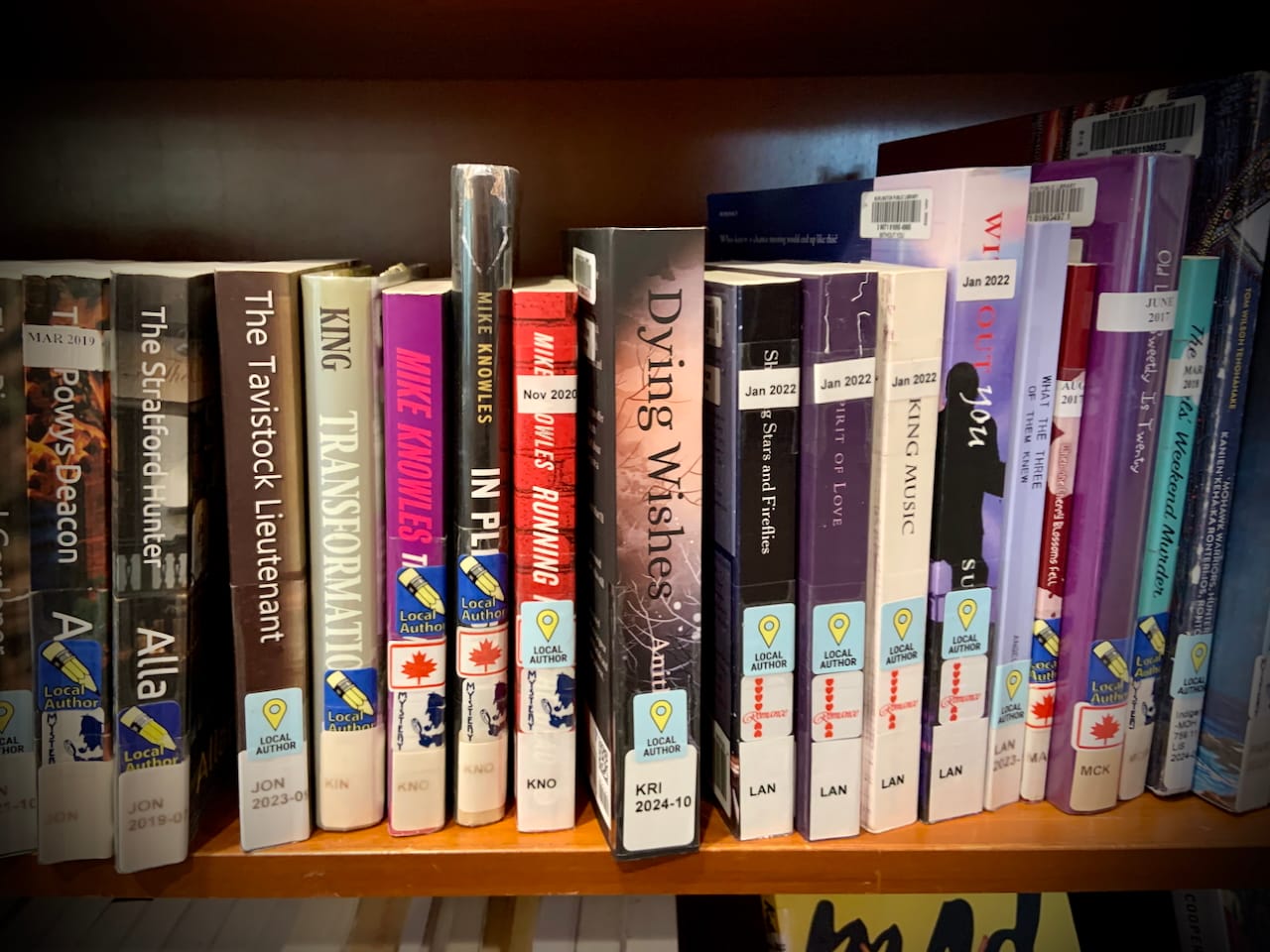

Another first for me is that one of my titles, Dying Wishes, now sits proudly on a shelf in the library in the Local Author Collection! All ready to be borrowed and read, if you have a BPL library card!

Dying Wishes is a contemporary fantasy novel set in Burlington and inspired by South Indian folklore.

It was a finalist for the 2023 Kobo Emerging Writer Prize in the Speculative Fiction category. The lovely folks at Kobo even did a wonderful interview with me at the time, which you can read here.

My child, D, was barely two years old when I started writing this story. One day he asked me about God and what happens after we die, and I didn't know how to answer him. I didn't want to feed him my beliefs and, worse still, I was undergoing a crisis of belief myself!

I had grown skeptical of the practices and traditions that my own parents followed, the ones I had accepted without questioning as a child.

And even though my parents didn't impose any of their beliefs on me as an adult, everything I had believed or subscribed to while growing up came unravelling when I was a new parent myself.

Thus began the tale of seven-year-old Ananya, the only child of a single mother who's handed the short end of the stick by the very Gods her mother stoutly worships.

In Ananya's own words ...

When I was seven, my mother died. I struck a bargain with the Gods to bring her back to life.

For thirteen years now, I have served as a Harbinger of Death, coaxing dying wishes out of mortals so that the God of Death may grant them moksha, liberation from the cycles of birth and death.

The man about to die this evening claims he has nothing to offer me. He is dying a content man, a rarity in our world.

But when the God of Death arrives to lead his soul away, the man changes his mind about dying and flees, surreptitiously planting on me an enigma.

I only know I cannot trust any God with this secret. And that I will pay an unbearable price for this concealment…

Come celebrate this little milestone in my writing journey with a 50% OFF on Dying Wishes over on my ebook store, Dream Pedlar Books!

(This offer is for email subscribers of Monthly Missives only. If you're not a subscriber yet, sign up now!)

And if you need a little more convincing, a dear reader recently wrote in after she watched the Netflix show Kaos, a modern-day re-imagining of Greek mythology.

"There were sooo many parallels and moments I thought of your writing," she said, in reference to Dying Wishes.

I wrote this book to explore my own thoughts on childhood and motherhood, on being an immigrant from India and making Canada my home, and on faith and spirituality. It became, quite literally, a quest for belonging across different worlds.

So grab your copy, and tell me what you think of the story!

Incidentally, I want to talk about community and belonging today.

My thoughts on this are still evolving, and in fact what I'm about to say below is in complete contradiction to what I shared just two months ago upon my return from India.

I hope this piece can help you reflect on what community and connection mean to you and turn into an ongoing exploration and discussion.

On community in fiction vs. community in the real world

So, I've been obsessed with friendship and community (or mostly the lack thereof) for decades now.

I thought I was the kind to seek deep, meaningful connection, and I took great pride in that self-image I held for a long time. I've been quick to put off small talk as insignificant and pointless.

And I believed that friendship between two people meant you trusted each other with your deepest, darkest secrets and counted on each other to have your back all the time.

Last month, in a moment of adulthood, it occurred to me that this was the fictional-world fantasy of relationships.

There's a saying among writers:

Reality is how the world is. Fiction is how the world should be.

We are drawn to stories of great courage and bravery, where love and friendship triumph over evil, where justice and hope prevail. Unless we're reading a tragedy, of course. Even so, a tragedy is a tale of loss incurred in the pursuit of a noble cause.

The reason we're drawn to these stories is because these values and ideals, which we hold so dear, are often at odds with what we see in reality. Because the real world is made of imperfect human beings like us, and make no mistake, we too are quite often the villain in somebody else's story.

On seeking community as a new parent

My obsession with community grew significantly after D was born. Every parenting expert was talking about how modern-day parenting in nuclear families was an exercise in insanity; they were all insisting that having that elusive 'community' was the key to raising emotionally healthy children.

Cue for panic to set in.

Because it was just the three of us here in Canada, with family being far away in India.

In those early days, I opened my doors to all, sometimes even strangers, inviting them over, naïvely assuming that if I gave what little I had, what little I could—my time and attention and affection—I'd get in return some of that friendship and community I was desperately hankering after.

Naturally (and mercifully, I now realize), few people took me up on those invitations, leaving me to worry that I was doomed to live a life of isolation, devoid of the kind of close friendships I read about in books and watched on Netflix.

Then the pandemic set in. It came as a great relief to me because now I had a genuine reason to give up my disastrous and failed attempts at finding a community to belong to.

In 2020—21, when two local authors got together to compile a book of essays on the pandemic, I wrote a piece titled 'Finding Self-Love in the Time of Coronavirus' (obviously a play on the title 'Love in the Time of Cholera'. Check out page 97 in this PDF version of the book, Writing The Rollercoaster: Stories of Riding Out the Pandemic in Burlington.)

In that piece, I wrote:

It took me a pandemic and the innate wisdom of my 4-year-old to understand that the most important relationship we can nurture in our lifetime is with ourselves. How we love and value ourselves shapes how we perceive the outer world and our place in it.

Socialization then simply becomes the ability to present our true, authentic selves to the world and embrace everyone for who they are.

It has little to do with whether or not we have friends and playdates, birthday parties and backyard barbecues.

It has everything to do with the ease with which we become our own best friend under all circumstances, irrespective of any external achievement or lack thereof, so that authenticity, and not desperation, drives our decisions and relationships.

~ An excerpt from 'Finding Self-Love in the Time of Coronavirus'

But sometimes the lessons we learn are short-lived.

As soon as schools resumed in full force, I was once again back on the hunt for a 'community', this time among other parents whose children attended the same school as D.

Eventually I had to acknowledge the fact that just because D has forged a good friendship with another child, it didn't mean that the respective parents have to become good friends too.

I now understand that I could have a lighthearted conversation with another parent at pick-up, but that wasn't going to translate into dropping in at each other's place over the weekends anytime soon.

But I railed against this reality for far too long. It seemed to me a strange way to live.

And my failed attempts at connecting in the way I thought was meaningful only made me feel more and more terrible about myself. I started to think that perhaps I wasn't wealthy enough or influential enough or popular enough for other parents to want to befriend me.

But what tormented me the most was the fear that D would pay the price for my 'failure' and grow up without a network of friends or a support system to rely on.

On understanding what this quest for community was really all about

Last week, I met a friend for the first time since university. I had last seen her more than 20 years ago, though we've stayed in touch somewhat through a common Yahoo group that then became a Facebook group and is now a WhatsApp group.

Right after uni, she had moved to the US for further studies and had lived there all this while, until she moved back to India two years ago. Naturally, we got talking about 'community' and life in North America vis-a-vis life in India.

We both shared how neither of us had ever wanted to be part of any large group of Indian friends who got together and celebrated festivals together, which is what most immigrants seem to do.

I mean, if I only wanted a large group of Indian friends, I'd have stayed in India. I was always driven to meet people from other places and learn about their lives. Our differences and similarities never cease to fascinate me.

Nevertheless, every time I saw people in large groups, FOMO would hit me hard and I'd worry I had gone down a completely wrong path in my life! Apparently, my friend felt the same way too.

The next day, it occurred to me—and I hastened to write to her—that I had been so fixated on having a network because I'd always been worried about who'd help little D in an emergency.

But when I thought about it, I realized that I do have a number of people I can call when in need, even though these are not the people I reach out to for day-to-day tasks or even for deep, meaningful connection!

This realization fell on me like a ton of bricks.

That not all friendships are equal, nor are they meant to be.

That all kinds of human interactions, ranging from casual to intimate, are a way of affirming each other's humanness.

That to trade one for the other or to consider one type of friendship or interaction better/worse than the other actually robs us of the ability to relate to the world at large in a healthy way.

On appreciating and cherishing the different kinds of human interactions we have

A couple of weeks ago, we got the call that every parent dreads. A call from school informing us that D had fallen in the playground at recess and had a head wound that wouldn't stop bleeding.

KrA and I rushed him to the hospital, where a very friendly doctor named Frank tended to D.

In the course of our conversation, Frank mentioned that when he studied medicine at university, he initially went into medical research. But then he realized that he missed the social aspect of interacting with people, so he chose to become a practising doctor instead.

We had a lovely interaction with Frank during the 20 or so minutes we spent with him. There were jokes about children's haircuts and other random stuff.

We're not going to become bosom friends—heck, I'd probably never even see him again in all my life—unlike in a fictional world where a chance encounter leads to something else and makes for an incredible story.

But the fleeting nature of such an interaction does not make it any less significant, and certainly doesn't take away from the joy and delight of sharing a moment in space and time with another person, even if our paths never cross again.

There was a time when, driven mad by my desperate desire for companionship and community, for acceptance and belonging, I refused to look at and say Hello or even smile at people I'd pass on my almost-daily walks along the bike path.

Perhaps it was the helplessness I felt at that time in my alone-ness, but I derived a certain sense of power in having the choice to look elsewhere and ignore a stranger on the street.

In refusing to put in the effort to acknowledge their existence, I naïvely thought I was preserving my own. After all, why should I be the one to validate their existence when my own felt far too small and insignificant?

One day, some ex-colleagues of KrA came down from Toronto to visit him, and they went out to the beach for an afternoon of barbecue. The first thing they noticed was how friendly people in Burlington were.

They were taken aback by the fact that a stranger passing by could flash a smile at you and acknowledge you, make you aware of your own beautiful existence on such a lovely afternoon by the beach.

"The small joys of running into an old co-worker or chatting with the bartender at your local might not be the first thing you think of when imagining the value of friendship—images of more intentional celebrations and comforts, such as birthday parties and movie nights, might come to mind more easily.

But Rawlins says that both kinds of interactions meet our fundamental desire to be known and perceived, to have our own humanity reflected back at us.

“A culture is only human to the extent that its members confirm each other,” he said, paraphrasing the philosopher Martin Buber.

“The people that we see in any number of everyday activities that we say, Hey, how you doing? That’s an affirmation of each other, and this is a comprehensive part of our world that I think has been stopped, to a great extent, in its tracks.”

~ An excerpt from The Pandemic Has Erased Entire Categories of Friendship by Amanda Mull in The Atlantic.

Some people we know are super interesting, they may have great stories to tell and amazing experiences to share. Interactions with them leave us feeling a little wiser, a little more open in our minds. But we may never know what their deepest desires and fears are, because they may never want to share that, and that's okay.

Then there are others who are reliable when it comes to matters of daily living. Like a Macedonian neighbour I had who didn't speak a word of English but kept offering D snacks and treats, and was happy to collect our mail when we traveled.

There are others too, like the parents I see while picking up D from school, and our conversations revolve mainly around our children and their activities. There's neither the time nor the inclination sometimes to get to know each other on a more personal or individual level.

And finally, after railing against this all these years, wrongly labelling it as a 'lack of community', I'm beginning to see that it's okay.

Conversely, I did manage to connect with one such parent of a child in D's class. D and M do not play with each other, but M's mom and I forged a bond irrespective of that. She was on maternity leave last year with her second child, and we often got together for coffee in the afternoons when our children were at school.

Then her maternity leave came to an end, and she went back to work. My work has ramped up too, and getting together for coffee on a weekday afternoon without the children to look after has become a luxury of the past we're no longer able to indulge in.

It was beautiful while it lasted, even if only for a brief season. Thinking that this friendship would have been more significant had it endured for longer is folly. It erases the beauty of what was in the mistaken belief that something deeper and longer-lasting would have been more life-changing or mattered more in some way.

In fiction, all these different characters are condensed into a single person or a small, tight-knit group, bound by the same cause, completely enmeshed in each other's lives.

But life is not fiction. And when we fail to appreciate the is-ness of life, its messiness and heartbreaks, the ebb and flow of people and relationships, we run the risk of chasing a fantasy, which is always a pursuit in vain.

It has also been liberating to realize, in the same vein, that I don't have to be everything for everyone as well.

I too play these different roles—being a mentor to someone, a confidante to another, an acquaintance to yet another person, a villain in someone else's life, or just a familiar face to countless others—and that is really all we can manage, given our limited time on this planet.

We simply cannot (and absolutely need not) be everything to everyone we meet.

On remembering and trusting in the wisdom of turning inwards rather than looking outwards for connection

We tend to highlight individualist cultures (such as those in the West) as selfish and are quick to laud collectivist cultures (such as those in the East) as far more communal and collaborative.

But in the course of that once-in-20-years conversation with my friend from university, we couldn't help but remark how here in North America we know many people who volunteer, participate in communal projects, and contribute to society.

And how India too is quite often a place where it's every man or woman for themselves, many people playing their respective roles in large groups (especially families) driven by their dysfunctional patterns (like people-pleasing or being overly nurturing) or out of a sense of disgruntled obligation.

In my early years, I grew up in a gated community where playdates were not a thing but the children sought each other out to play while the mommies (most of whom didn't go to work) ran their households and got together and chatted and the daddies went to work and earned a living.

But you see, everybody knew everybody else's business.

There was also a lot of gossip and drama, both among the group of adults as well as among the group of children, as is wont to happen in large groups.

People were more prone to gossip and whine about others than actually look to solve any problems they had with the person in question. My wise friend from uni calls this 'trauma-dumping'!

I now see that it was merely a crowd, and we called it community, for what it was worth.

Which makes me question why we (perhaps it's only those of us living in the west as I do) are inclined to believe that living in a community is the panacea for all our mental health issues. Perhaps, because the grass appears greener on the other side?

I say this not to diss one type of life/society/culture nor to approve of the other, but having spent nearly equal parts of my life in each of these two extremes, trying and sometimes finding but more often failing to find some sort of a happy middle, I have to concede that maybe the answer lies not in the outer constructs of society.

The only place we can really turn towards is inwards.

Unless we are whole and connected to ourselves, we'll always look towards external relationships—romantic love, friendship, family, community—to fulfil us.

And naturally that's going to disappoint, especially since the other person is looking to us to do the same for them, fulfil their unmet inner needs.

It is only when we put in the effort to grow and own ourselves wholly, that we can even begin to find others, similarly self-assured, to share a few moments with us on the ride.

Shel Silverstein's The Missing Piece Meets The Big O explains this in a fascinating way.

There's a wedge-shaped missing piece, sitting alone and "waiting for someone to come along and take it somewhere."

It thinks it can't roll by itself because of its sharp corners and angular shape.

It meets a lot of 'someones', each misshapen in their own way, each missing some part of themselves, only to realize that trying to fit together with them is almost always futile in the long run, even if at first it felt as though they'd make a really good match.

Then, wonder of all wonders, comes a piece without any missing pieces! It calls itself the Big O.

“I think you are the one I have been waiting for,” said the missing piece. “Maybe I am your missing piece.”

“But I am not missing a piece,” said the Big O. “There is no place you would fit.”

“That is too bad,” said the missing piece. “I was hoping that perhaps I could roll with you…”

“You cannot roll with me,” said the Big O, “but perhaps you can roll by yourself.”

What a lesson in personal growth! And equally, what a lesson in setting boundaries!

Read the book over at The Marginalian to see how the rest of the story unfolds.

So write to me and let me know what your thoughts are and what your experiences have been in the pursuit of community in your part of the world. It's a universal theme we can all relate to, no matter what our views and opinions are.

Tales for Dreamers

I have four lovely tales, all Halloween-themed, and you can find the collection here. These stories feature carved pumpkins, a talking mask, a werewolf in a supermarket, and mysterious neon handprints.

Books You May Love

I'm realizing only now that I haven't read much this month. The days have gone in meeting friends, attending events at D's school, preparing for Diwali and Halloween (which fall on the same day this year!), and also in watching more Netflix than usual, so reading fell by the wayside.

I did read a YA book, I kissed Shara Wheeler, by Casey McQuiston. In this tale, Chloe's rival for valedictorian, Shara Wheeler, kisses her and then simply disappears, leaving behind clues for Chloe and two other schoolmates to find.

There was a mystery element to it, and the cast is very diverse, and it was a fun read overall in a month that was rather busy with life stuff!

Well, so this has perhaps been my longest missive so far, dear Dreamer! Thank you for staying with me this far.

Sometimes I learn something about life and it splits my head open in such a way that I have to share it with you, in the hope that somewhere in those words you too will find the encouragement to look at your own life and jettison what no longer works for you while embracing what does.

Next month, I turn a year older! And I have a fairly good idea what I'm getting myself for a birthday present. I'll tell you all about it in November's missive.

And don't forget. If you'll be in/around Burlington on Sunday, 17 November, come hang out with me at the library! We'll talk writing, books, publishing, life! Just like we do in these missives.

Until November's end then,

Anitha