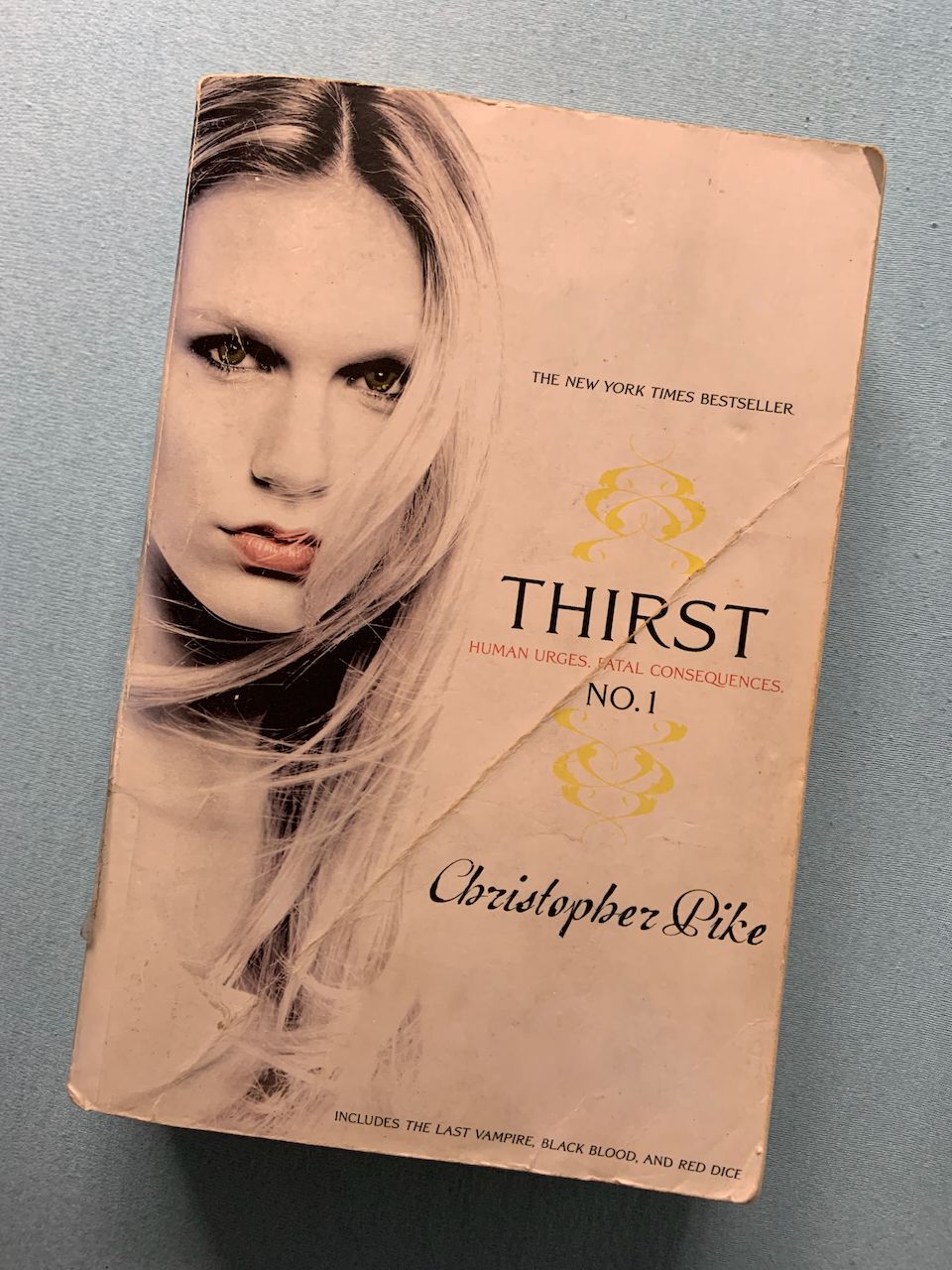

books you may love: Thirst series by Christopher Pike

"Krishna means love," she said. "But Radha means longing. Longing is older than love. I am older than he. Did you know that, Sita?" ~ Thirst series by Christopher Pike

Several weeks ago, my very dear friend and bringer-of-good-things-and-joy-in-my-life, Helen, asked me if I had read any books by the author Christopher Pike.

I immediately looked up Pike on Google and saw that he was the author of The Midnight Club, which is a young adult supernatural horror series currently streaming on Netflix. A bunch of terminally ill young adults live in a hospice and they meet up at midnight to tell each other scary tales.

I had watched two episodes, and I consider that a great achievement on my part, so easily spooked I am. But I was too scared to watch further although I had enjoyed what I watched.

Helen referred me to another series of YA books by Pike, initially released as The Last Vampire, later rebranded as Thirst. It is about a 5,000-year-old vampire named Sita, she said, which immediately intrigued me.

And when my dear friend said that the series "planted in her a lifelong curiosity and passion for all things Indian," I had to read it. She did warn me though that it was written by a white guy in the 1990s although she found that he wove the gods and myths in the story with much love.

After hearing that, the first book that came to my mind was Boy Swallows Universe by Australian writer, Trent Dalton.

While I loved that book, and I read it a really long time ago, I remember the one little annoyance that stuck out like a sore thumb for me was the feeling of not being very satisfied with the reference to Krishna and his story of swallowing the Universe.

Maybe I missed the point but for a book that was titled after that story of Krishna, I couldn't quite understand the relevance of it although critics and reviewers have lauded the tale and the reference to the blue Hindu God. Hinduism goes mainstream, reads one such glowing review. But I found that the reference to Krishna's story itself only got a brief mention, which the book could have done without and still remained a fantastic tale.

Nevertheless, I picked up Thirst with an open mind and with great faith in Helen's recommendation, and I completely, madly, utterly, absolutely, irreversibly, unequivocally fell in love with it.

A little context first. Growing up, between the two most important epics of Hinduism, I much preferred Mahabharata to Ramayana and I never quite took to the character of Sita in the latter.

She came across to me as a very passive character; this may partly be due to the fact that much of my knowledge of these two epics came from TV and Ramayana was certainly telecast as a very slow-moving series that my 8- or 10-year-old self didn't have much patience to sit through.

But in Thirst, Sita is this old soul, but also a young blonde-haired, blue-eyed woman, who has lived as a vampire for more than 5,000 years with superhuman strength and the looks of a gorgeous teenager. In the first book in the series, titled The Last Vampire, Sita's creator Yaksha is seeking her out to kill her.

Alongside the unfolding of the plot in the present day, we learn about how Sita became a vampire and her breed's encounter with Krishna. Yes, the very Krishna, the Lord of the Universe.

Reading The Last Vampire made me fall in love with Hindu philosophy and gods in a way that growing up in India in a Hindu family couldn't. Somehow, Pike has reached out and touched the essence of who Krishna is, what his divinity means, and he portrays these with heartbreaking tenderness from the point of view of Sita.

For instance, the lines below are Sita's remembrance of the first time she encountered Krishna. Sita and Yaksha have captured Radha, and are waiting for Krishna to come and engage in a duel.

We were all waiting. In that moment, even though I was not yet seventy years old, I felt as if I had waited since the dawn of creation to see this person. I who held captive his great jewel.

Krishna came out of the forest.

He was not a blue person as he was later to be depicted in paintings. Artists were to show him that way only because blue was symbolic of the sky, which to them seemed to stretch to infinity, and which was what Krishna was supposed to be in essence, the eternal infinite Brahman, above and beyond which there was nothing greater. He was a man such as all men I had seen, with two arms and two legs, one head above his shoulders, his skin the colour of tea with milk in it, not as dark as most in India but not as light as my own. Yet there was no one like him. Even a glance showed me that he was special in a way I knew I would never fully comprehend. He walked out of the trees and all eyes followed him.

He was tall, almost as tall as Yaksha, which was unusual for those days when people seldom grew to over six feet. His black hair was long—one of his many names was Keshava, master of the senses, or long-haired. In his right hand he held a lotus flower, in his left his fabled flute. He was powerfully built; his legs long, his every movement bewitching. He seemed not to look at anyone directly, but only to give sidelong glances. Yet these were enough to send a thrill through the crowd, on both sides. He was impossible not to stare at, though I tried hard to turn away. For I felt as if he were placing a spell over me that I would never recover from. Yet I did manage to turn aside for an instant. It was when I felt the touch of a hand on my brow. It was Radha, my supposed enemy, comforting me with her touch.

"Krishna means love," she said. "But Radha means longing. Longing is older than love. I am older than he. Did you know that, Sita?"

Krishna did not look directly at Radha or me. Yet he was close enough so that I could hear him speak. His voice was mesmerizing. It was not so much the sound of his words, but the place from which they sprang. Their authority and power. And, yes, love, I could hear love even as he spoke to his enemy. There was such peace in his tone. With all that was happening, he was not disturbed. I had the feeling that for him it was merely a play. That we were all just actors in a drama he was directing. But I was not enjoying the part I had been selected for. I did not see how Yaksha could beat Krishna. I felt sure that this day would be our last.

And these lines below are on the duel between Yaksha and Krishna. I read these passages over and over again, amazed at the beauty in these lines, my heart singing at the essence of Krishna that Pike has so beautifully captured, my soul filled with a longing, a longing for Krishna, a longing for a world in which Krishna can come and pull out his flute and start playing his notes and simply make all the chaos settle down.

I tried to choose only a few lines to share here, but I couldn't bring myself to chop up the paragraphs.

Finally, close to dark, Yaksha and Krishna climbed into the pit. Each carried a flute, nothing more. The people on both sides watched, but from a distance as Krishna had wanted. Only Radha and I stood close to the pit. There had to be a hundred snakes in that huge hole. They bit each other and more than a few were already being eaten.

Yaksha and Krishna sat at opposite ends of the pit, each with his back to the wall of earth. They began to play immediately. They had to; the snakes moved for each of them right away. But with the sound of the music, both melodies, the snakes backed off and appeared uncertain.

Now, Yaksha could play wonderfully, although his songs were always laced with sorrow and pain. His music was hypnotic; he could draw victims to feed on simply with his flute. But I realized instantly that his playing, for all its power, was a mere shadow next to Krishna's music. For Krishna played the song of life itself. Each note on his flute was like a different center in the human body. His breath through the notes on the flute was like the universal breath through the bodies of all people. He would play the third note on his flute and the third center in my body, at the navel, would vibrate with different emotions. The navel is the seat of jealousy and attachment, and of joy and generosity. I felt these as he played. When Krishna would blow through this hole with a heavy breath, I would feel as if everything that I had ever called mine had been stripped from me. But when he would change his breath, let the notes go long and light, then I would smile and want to give something to those around me. Such was his mastery.

His playing had the snakes completely bewildered. None would attack him. Yet Yaksha was able to keep the snakes at bay with his music as well, although he was not able to send them after his foe. So the contenst went on for a long time without either side hurting the other. Yet it was clear to me Krishna was in command, as he was in control of my emotions. He moved to the fifth note on the flute, which stirred the fifth center in my body, at the throat. In that spot there are two emotions: sorrow and gratitude. Both emotions bring tears, one bitter, the other sweet. When Krishna lowered his breath, I felt like weeping. When he sang higher I also felt choked, but with thanks. Yet I did not know what I was thankful for. Not the outcome of the contest, surely. I knew then that Yaksha would certainly lose, and that the result could be nothing other than our extinction.

Even as the recognition of our impending doom crossed my mind, Krishna began to play the fourth note. This affected my heart; it affected the hearts of all gathered. In the heart are three emotions—I felt them then: love, fear, and hatred. I could see that an individual could only have one of the three at a time. When you were in love you knew no fear or hatred. When you were fearful, there was no possibility of love or hate. And when there was hate, there was only hate.

Krishna played the fourth note softly initially, so that a feeling of warmth swept both sides. This he did for a long time, and it seemed as if vampires and mortals alike stared across the clearing at one another and wondered why they were enemies. Such was the power of that one note, perfectly pitched.

Yet Krishna now pushed his play towards its climax. He lowered his breath, and the love in the gathering turned to hate. A restlessness went through the crowd, and individuals on both sides shifted this way and that as if preparing to attack. Then Krishna played the fourth note in a different way, and the hate changed to fear. And finally this emotion pierced Yaksha, who had so far remained unmoved by Krishna's flute. I saw him tremble—the worst thing he could do before a swarm of snakes. Because a serpent only strikes where there is fear.

And then there is that part in which we see the Krishna as Sita knew him and the Krishna that the rest of the world, especially 1990s America knows. Below are the lines in which Sita talks about Krishna to a character named Ray Riley.

"You remind me of someone."

"Who?"

"My husband, Rama. The night I was made a vampire, I was forced to leave him. I never saw him again."

"Five thousand years ago?"

"Yes. I knew Krishna."

"Hare Krishna?"

The moment is so serious, but I have to laugh. "He was not the way you think from what you see these days. Krishna was—there are no words for him. He was everything. It is he who has protected me all these years."

There's a universality in all this that brings together an author's words, a friend's love, and my heart's longing for something undefinable, something made so conspicuous by its absence that I've spent a lifetime looking for it.

Sometimes I find it in the writing of words and feelings, in between the pages of a beautifully written book such as the one above, in the moments spent in the presence of a friend, in the complete abandon I witness in my child's play, in the notes of melodious music, in the strokes and colours of a bewitching painting.

But even those are fleeting; it is as if they light a spark but not strong enough for it to become a raging fire and consume me. The little flame is very easily doused the instant I come back to the real world. Which begets the question: what is real, and what is the illusion?

I reckon if I'm looking for something eternal, something more lasting, I'll just have to call this unnameable feeling Krishna and leave it at his feet. All the cleverness and intelligence in this world are inadequate to answer these questions and the only choice we are truly left with it is to stop asking them in the first place, stop demanding to be convinced and take a leap of faith instead.

Go ahead and give Thirst a read, and we'll spend several evenings and twilights together, silently consumed by its beauty.

Feature Image Attribution: Photo by Mohamed Arif on Unsplash