the art of 'hiraeth'

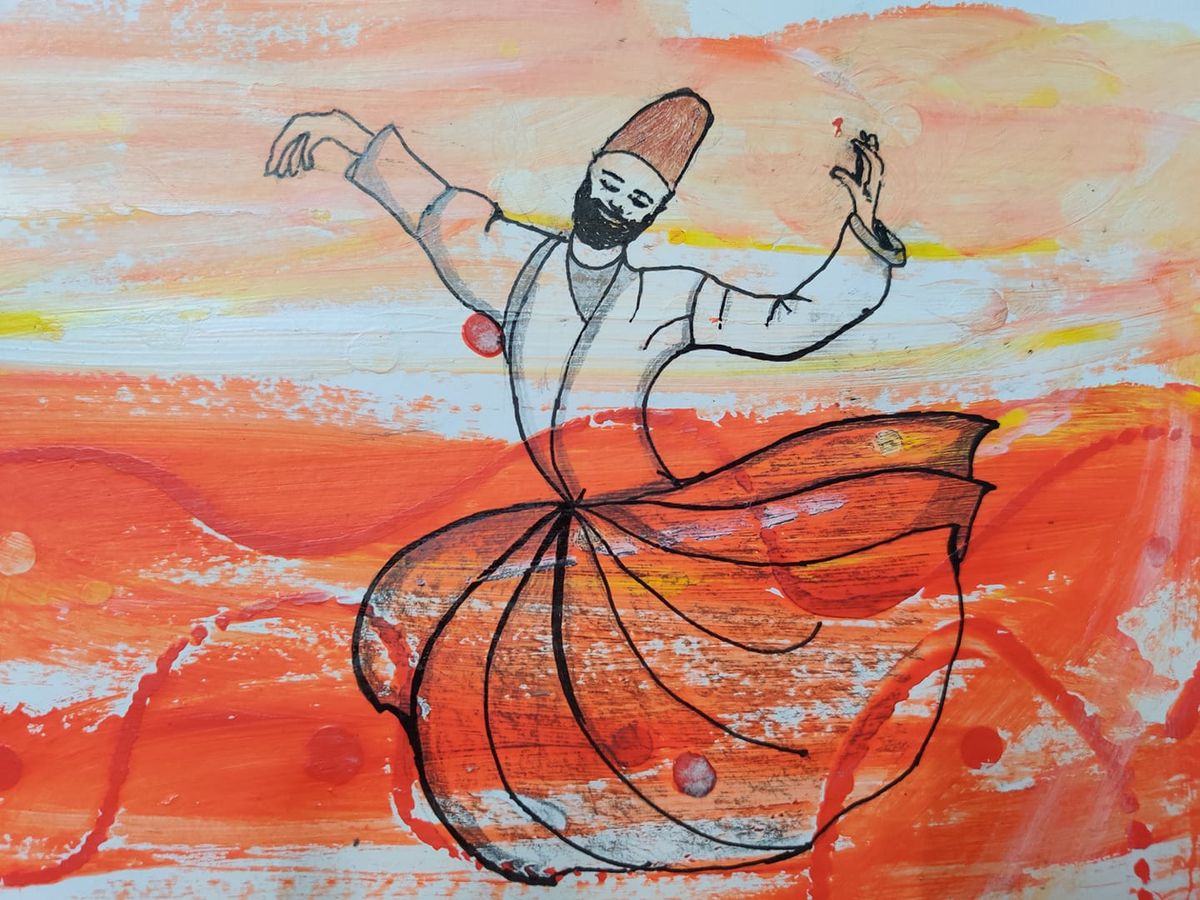

(Artwork by dear friend, Padmaja Balaji)

A fortnight ago, I came across and started to read an enchanting book titled 'The Art of Inheriting Secrets' by Barbara O'Neal. It's about a California-based food editor, Olivia Shaw, who inherits an English estate and a title when her mother dies, both bequests her mother had never mentioned in her lifetime.

This is the type of book I usually find myself gravitating towards. Family secrets. Old homes. The past a mystery. The present a dilemma. Both unravelling in their own way.

But the thing that came as an unexpected and wonderful surprise was the inclusion of a British-Indian character, Samir, who plays a very prominent role in the story. Romance blooms between Olivia and Samir, whose sister runs an Indian restaurant in the village.

So there are ample descriptions of Indian food, Tagore is quoted a few times, the concept of social class in Britain is explored from Samir's perspective. The very prominent Indian element in the story amped up the enchantment factor for me by several orders of magnitude.

Shortly after I had finished reading this book, another one fell into my lap. The Henna Artist by Alka Joshi. I can't even begin to describe how much I loved this book.

In 1950s Jaipur, seventeen-year-old Lakshmi runs away from an abusive marriage and makes her way to Jaipur (after a brief stint in Agra), where she earns a living by making henna designs for the city's affluent class. She's also a confidante, privy to the secrets of the wealthy, plays matchmaker, and is well-versed in the art of herbal medicine, which she uses to help cure women of their many ailments, ranging from depression to infertility to unwanted pregnancies.

But one day, her ex-husband catches up with her along with her sister, a sibling Lakshmi never even knew she had. Her sister gets into all sorts of trouble, and the life that Lakshmi has built so carefully for more than a decade threatens to crumble.

Lakshmi is such a strong character in the story, doing what it takes to survive the patriarchy, hobnobbing with the wealthy while constantly being mindful of her own plebeian status in the social strata.

Joshi's descriptions of the city of Jaipur, of the ways of the Oxford-educated Indian men and their numerous dalliances, of the gossip-y ways of their wives, and the whole 'boys will be boys, and it's always the girl's fault' ethos that underpinned the Indian society back then (and even now in many parts) were so apt and beautifully done I just didn't want the story to end. Looks like there's going to be a sequel to the story, and I can't wait to get my hands on it.

I read these books at a time when I was beset with a lot of doubt about all the Indian, especially Tamilian, elements, that had seeped into Dying Wishes.

In the novel, Infinity's mother, a character referred to as Amma in the book, moved from India to Canada as a single mother with her four-year-old. But her life within the four walls of their home is largely an attempt at recreating the world she had left behind. Her nostalgia seeps into the foods she cooks, the Gods she worships, and the temple she visits. The only friends she has are Indian, and she detests Halloween with as much passion as she loves Diwali/Deepavali, choosing to celebrate the latter according to the time in India.

Amma's nostalgia in the novel stems in large part from my own. But it's funny – this pining for the place of my childhood – because for as long as I lived in India, I'd only yearned to run away from there.

But until fairly recently, for as long as I've lived abroad, I've pined for my homeland, not the present one, but the one of my early childhood, when I was still full of ambition and naive hope and unbridled optimism for the future, my future.

Every visit to India used to be a stark reminder of how the land I held in my dreams, in my heart, no longer existed, but had morphed into something very unfamiliar, more foreign than the distant lands I had come to call home by then.

Later, I realised it wasn't a motherland that I missed, it was family. Each visit reminded me of how much older my parents had grown, and my aunts and uncles too, and the little cousin brother and cousin sister, babies of the family, were suddenly grown-ups. And in these new avatars, there was little of their former selves that I had adored and remembered.

While I was pining for a land of my memories and reminiscences, I hadn't understood that it existed only in my head and nowhere else. And this was true of the people too.

The fantasies I had built in my head of my interactions with them, both in the past and in the future, were solely mine. A fantasy future built on an embellished past, and bearing little resemblance to reality when it arrived.

Then what was I truly pining for?

After decades of walking around with this gaping hole in my heart, always feeling like something is amiss, I can only think of one thing – a sense of belonging.

And of course I looked for belonging everywhere outside – the places I grew up in, the people I grew up with, the places I worked at. And the only place I eventually found it was within me.

I reckon when we're born, we never question our right to exist in this world, in the place we arrive at, in the people entrusted with our care. As we grow up, these convictions come into question so often, we feel the need to get away from the old and the familiar to explore the new and the strange, in the hopes that it may reveal something amazing about us, about who we are and what we want.

But eventually, every place begins to resemble the other. Every interaction leaves us feeling jaded.

When I was in college, I fell in and out of 'love' with so many people in such rapid succession, I remember telling a friend in my final year or so, "This too will pass. I'll feel this way for a few days, and this crush too will become history."

This nugget of self-understanding had struck me as extremely poignant and moving back then.

That same infatuation lingered with places and jobs and hobbies until everything eventually just felt like some random filler I was using to plug that hole in my heart.

Until D arrived, that is.

I've often written how motherhood has quite literally been the most significant spiritual journey of my life. It has made me question everything I thought I knew or believed about life and God, spirituality and relating, all my notions of good and bad or right and wrong. It made me throw out the old ways of thinking and has helped me uncover an authenticity I had long forgotten I owned and, more importantly, the courage to be true to myself.

I've spoken up when I'd have normally kept quiet in order to maintain peace. I've defied culture when I've found it demeaning or segregating human beings as 'greater than' or 'lesser than', 'superiors' or 'inferiors'.

But nearly four decades of hardwiring is not reversed overnight. While every moment is an opportunity to choose anew, it also holds the peril of slipping back into old patterns and beliefs.

And this is one of the things that jolt me out of deep sleep at 2 A.M. and keep me awake for the next three hours.

I'm afraid I'd default to my old self, because to hold my ground firmly, respectfully, would require a calm conviction, and the two states – calmness and conviction – have been antithetical to each other for so long that I worry I'd either compromise on my authenticity or lose my composure entirely.

I can apply that insight to every aspect of my life – relationships, setting boundaries, financials, writing – and it is astounding how accurate it is.

Take 'Tales for Dreamers' for instance. I've had such a start-stop affair with it, and even now, not a week goes by when I haven't thought at least a handful of times whether I should continue with it or not. I've abandoned it so many times that even now that I've resumed it, I'm constantly wondering if I should keep going.

But when I leave those questions aside, I find that each tale, when I write it, comes from a place of unbridled joy. This is one project that could be called a 'labour of love', though frankly there is no 'labour' involved. I can trust the image will present itself of its own accord, that I'll find something catchy, quirky, in my meanderings, and that the story too will flow from the ether, deep into me, and out on the screen.

I realise now that fear and self-doubt – both pertaining to my art and to myself – may well continue to nag me for as long as I live. And maybe, just maybe, I'm beginning to get used to them being my allies without wishing them away or letting them interfere with my work.

At the time I sent 'Dying Wishes' out into the world, I came across Osho's opinions on objective art. Below is an excerpt from A Genius in Exploitation, Chapter 26 of The Last Testament (Vol. 30). This is what he says in his trademark outrageous fashion with much humour and mirth.

Art can be divided into two parts. Ninety-nine percent of art is subjective art. Only one percent is objective art. The ninety-nine percent subjective art has no relationship with meditation. Only one percent objective art is based on meditation.

The subjective art means you are pouring down your subjectivity on the canvas, your dreams, your imaginations, your fantasies. It is a projection of your psychology in the same way it will be in poetry, in music, in all dimensions of creativity. You are not concerned with the person who is going to see your painting. You are not concerned what will happen to him when he sees your painting; that is not your concern at all.

Your art is simply a kind of vomiting. It will help you, just the way vomiting helps. It takes the nausea off, makes you cleaner, makes you feel healthier. But you have not considered what is going to happen to the person who is going to see your vomit. He will become nauseous. He may start feeling sick.

Look at the paintings of Picasso. He is a great painter, but just a subjective artist. Looking at his paintings, you will start feeling sick, dizzy, something going berserk in your mind. You cannot go on looking at Picasso's paintings long enough. You would like to get away, because the painting has not come from a silent being. It has come from a chaos. It is a by-product of a nightmare. But ninety-nine percent of art belongs to that category.

Objective art is just the opposite. The man has nothing to throw, he is utterly empty, absolutely clean. Out of this silence, out of this emptiness, arises love, compassion, and out of this silence a possibility for creativity. This silence, this love, this compassion, these are the qualities of meditation. ~ Osho

He then goes on to explain what he means by objective art.

Meditation brings you to your very centre, and your centre is not only your centre, it is the centre of the whole existence. Only on the periphery we are different. As we start moving towards the centre, we are one. We are part of eternity, a tremendously luminous experience of ecstasy, which is beyond words, something that you can be but very difficult to express it. But a great desire arises in you to share it, because all other people around you are groping for exactly such experiences. And you have it. You know the path.

And these people are searching everywhere except within themselves – where it is. You would like to shout in their ears. You would like to shake them and tell them that "Open your eyes! Where are you going? Wherever you go, you go away from yourself. Come back home, and come as deep into yourself as possible."

This desire to share becomes creativity. Somebody can dance. There have been mystics – for example, Jalaluddin Rumi – whose teaching was not in words, whose teaching was in dance. He will dance. His disciples will be sitting by his side, and he will tell them that "Anybody who feels like joining me can join. It is a question of feeling. If you don't feel like, it is up to you. You can simply sit and see."

But when you see a man like Jalaluddin Rumi dancing, something dormant in you becomes active. In spite of yourself, you can find you have joined the dance. You are already dancing before you become aware you have joined it.

Even this experience is of tremendous value, that you have been pulled like a magnetic force. It has not been your mind decision, you have not weighed for pro or for against, to join or not to join, no. Just the beauty of Rumi's dance, his spreading energy, has taken possession of you. You are being touched. This dance is objective art. ~ Osho

I didn't quite understand his words at first. And then I remembered something, which drove home the point for me.

A while ago, my friend Padmaja Balaji put up her artwork on Facebook. Just the sight of the dancing Sufi was such a salve for my restless heart. In the days that followed, I kept admiring how a few simple lines easily conveyed the beatific expression of the dancer.

When I read Osho's words, this was the image that popped up in my mind. To me, this is truly an example of objective art, that makes me want to lose myself in it. Rejoice and celebrate with the dancer. I don't even need any music.

There is no need for analysis. You could look at the curve of his body, the swirl of his robe, and find that everything makes this picture an immaculate personification of dance itself. You could copy these exact strokes and still the replica will be missing the essence of silence and meditation that make Padmaja's art what it is.

This brings us back to that debate on calmness vs conviction in the pursuit of art. A month or so ago, my struggle between conviction and calmness came to a head, the reasons of which merit another post in itself. In brief, I wanted to 'conquer' a writing practice, one that would enable me to reach my word count goals on a daily/weekly basis. But it was like war.

At the very least, I believe that our pursuit of art ought not to be making life miserable for ourselves or for others. If it is, we're better off doing something else.

So I had no choice but to sit with everything that was cropping up, not writing, not doing much else really other than the things that need to be done on a day-to-day basis for the sake of mere survival. I was often lying in bed and staring out at the blue skies and white clouds. Tara Brach's Radical Acceptance kept me company and helped me simply be.

And it dawned on me that the more we dip into the well of silence and trust and compassion, the more and more our work becomes a salve, a refuge, a mirror for ourselves and also for the beholder. It becomes quite uplifting. Inspiring. Not something that induces envy or competition or fear.

Art then becomes such a soothing expression of the self it can hold the artist and the world in a sacred place of simply being. A place without judgement. A place without self-flagellation. A place where one comes back to encounter oneself, to embrace one's own self in radical acceptance.

Children are such a natural expression of the kind of acceptance we seek for a lifetime. It took me five years of living with D to understand and accept myself. To understand myself, as I was back when I was just as small. To understand myself now, all that I am now.

The other day, our neighbour's parents had come to visit her. D was playing in the front yard. They parked their car on one side of the yard and had to walk to the other side to get to their daughter's place. D said Hello to them and they had a little chat, and they came a little close to D en route to their daughter's place, and he promptly said, "Please don't come too close to me because of the coronavirus." Just a statement of fact. No judgement involved on his part.

I was indoors and had just stepped into the yard when I caught these words of his. I would never admonish him for saying what was on his mind, but my first instinct was to make some gesture of apology behind his back, but luckily, luckily, luckily, something in me stopped me from betraying my child thus.

And I was so proud of him in that moment for saying what was on his mind, with simplicity and sincerity, and without fear of retribution, fear of offending, or fear of being misunderstood. I've bit my tongue so many times in an attempt to keep peace without realising that (i) the other person's reaction is not at all in our control, and (ii) every time I thought I was 'keeping peace', I was in fact betraying myself, waging war with myself.

And now, when I'm putting myself first, that part of me that had gotten used to being treated like she was worthless first raises a hand in doubt and says, "Are you sure? Are you sure you will not let me down again?" And that makes me more resolved to honour myself, first and foremost. From that place of self-acceptance and stillness, art will flow without any coercion.

These are life-lessons I learnt from being with D. Every night at bedtime, I tell him how lucky I am that he came into my life.

I remember when I started 'Tales for Dreamers' in its earliest avatar more than a decade ago, inspired by Erin Morgenstern's flax-golden tales, I thought I'd find that kind of magic in the suburban neighbourhoods of North America. I didn't, obviously. It broke my heart when I found out that I had travelled halfway across the world only to feel as if I had left behind whatever little magic I had once held.

Now, as I walk new paths, I find that magic in the very place every mystic says it lies, waiting to be found. Inside of me. Though for the longest time, I had felt I was too wretched for that to be true. But that's where it has been. And it shows up in the world outside of its own accord without any manipulation or engineering on my part.

When stuff like that happens, life feels easy. Effortless. Worthwhile. The universe conspiring forces. Everything I need making its way towards me. All that magic. With so much tenderness.

'Hiraeth' then feels like just another long, long journey I undertook to find my way back to my one true home, my own self. Here. Now.

I'll leave you with an excerpt from Tara Brach's Radical Acceptance, in which she quotes a contemporary Indian master, Bapuji. I don't know who he is but his words below, as they appear in Tara's book, give me much solace.

My beloved child,

Break your heart no longer.

Each time you judge yourself you break your own heart.

You stop feeding on the love which is the wellspring of your vitality.

The time has come, your time

To live, to celebrate and to see the goodness that you are ...

Let no one, no thing, no idea or ideal obstruct you

If one comes, even in the name of "Truth", forgive it for its unknowing

Do not fight.

Let go.

And breathe — into the goodness that you are.

~ Bapuji, contemporary Indian master, as quoted in Tara Brach's Radical Acceptance