books you may love: DS Harbinder Kaur series & Inspector Persis Wadia (Malabar House) series

Spreading book cheer in the world, and some enlightening thoughts on diversity and representation in fiction!

What a delight these past few days have been in terms of all the reader pleasure I've indulged in!

It all began with a visit to the library a few weeks ago. I was browsing through the shelves that held mysteries written by JD Robb (a pseudonym for prolific and popular author, Nora Roberts), looking for the first book in a (so far) 52-book series titled Naked in Death, when one of the librarians who was stocking the shelves came by and asked me if I needed any help.

At first, I politely declined, but then I asked her if Naked in Death was available. She looked up on her mobile system; it wasn't.

But that sparked the beginning of a long conversation about books and TV shows. We shared so many favourites: the Inspector Ian Rutledge series by Charles Todd, the Cormoran Strike novels by Robert Galbraith (JK Rowling), the Murdoch Mysteries TV show, which is a long-standing Canadian favourite.

Of course, the conversation then drifted towards British authors, and the librarian took me over to another aisle (our library has several aisles devoted to mystery!) and picked up a book by an author named Elly Griffiths.

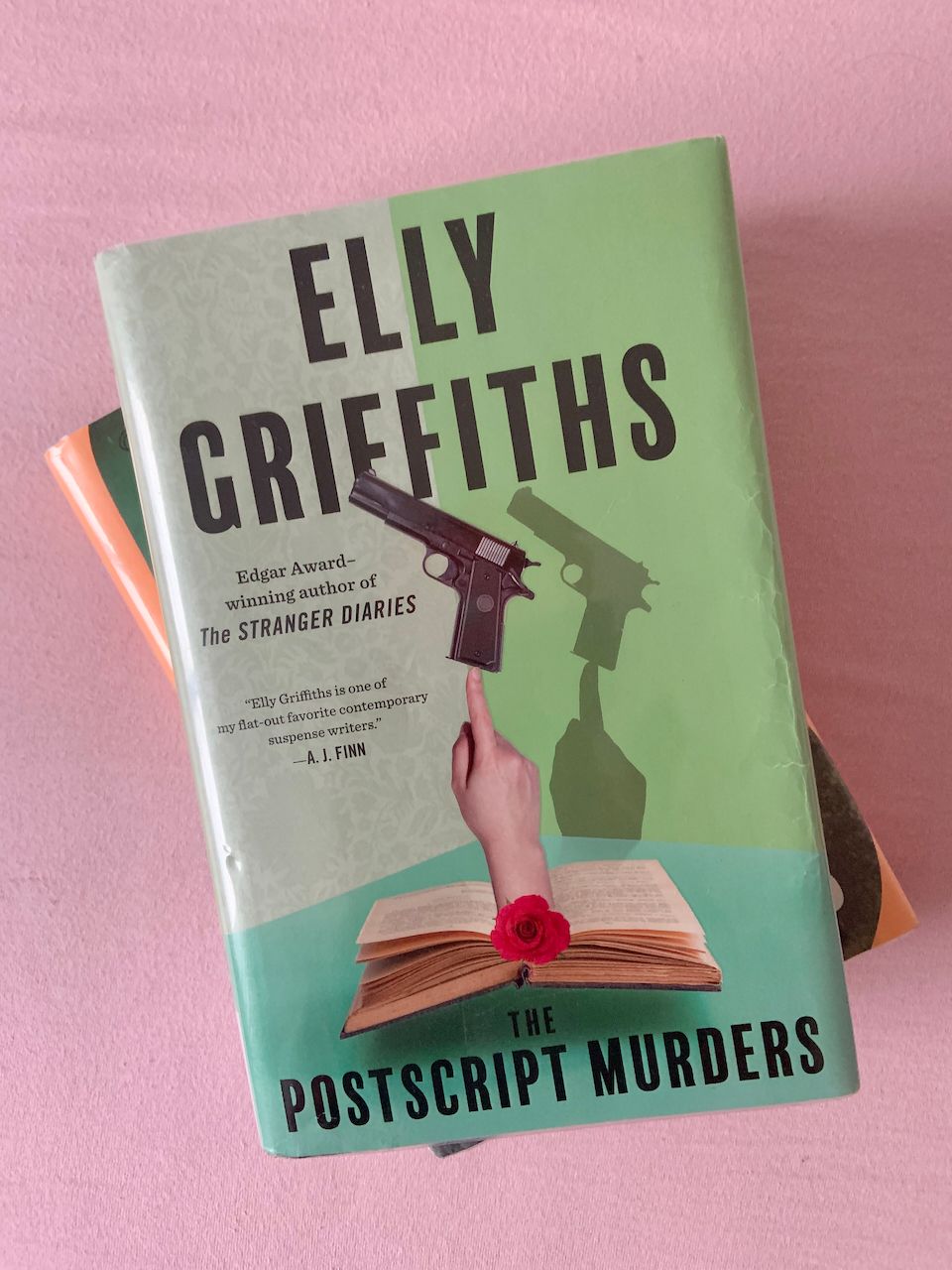

Griffiths is known for her Dr. Ruth Galloway mysteries, the librarian told me, Galloway being a forensic archaeologist! The first book in the series was not on the shelf, so the librarian pointed me to another of Griffiths' books, this one titled The Postscript Murders, in which the investigating officer was a Detective Sergeant Harbinder Kaur!

That completely piqued my interest, and even though it was the second book in the series, I didn't mind reading it.

And wow, have I fallen in love with DS Kaur! She's a second-generation immigrant, in her mid-30s, living with her parents in England, unmarried, and also gay. And she loves playing Panda Pop on her mobile phone!

Kaur has an endearingly wry sense of humour, and Griffiths masterfully weaves in a funny sentence or two in the most unexpected of places, which made me stop and laugh and simply soak up the simple delight of reading a good book with quirky characters with varied backgrounds.

In The Postscript Murders, a 90-year-old woman, Peggy Smith, dies of apparent heart failure but her carer, a Ukrainian woman named Natalka, finds her death suspicious and reaches out to DS Kaur to investigate.

'We need to find out what it means before we decide if it's suspicious,' says Harbinder. 'And why does it say M. Smith? I thought you said her name was Peggy.'

'Peggy is sometimes short for Margaret,' says Natalka. 'English names are odd like that.'

'I am English,' says Harbinder. She's not going to let Natalka assume otherwise, just because she's not white.

'I'm Ukrainian,' says Natalka. 'We have lots of strange names too.'

~ The Postscript Murders by Elly Griffiths

The book is filled with many hilarious yet deeply perceptive observations such as these.

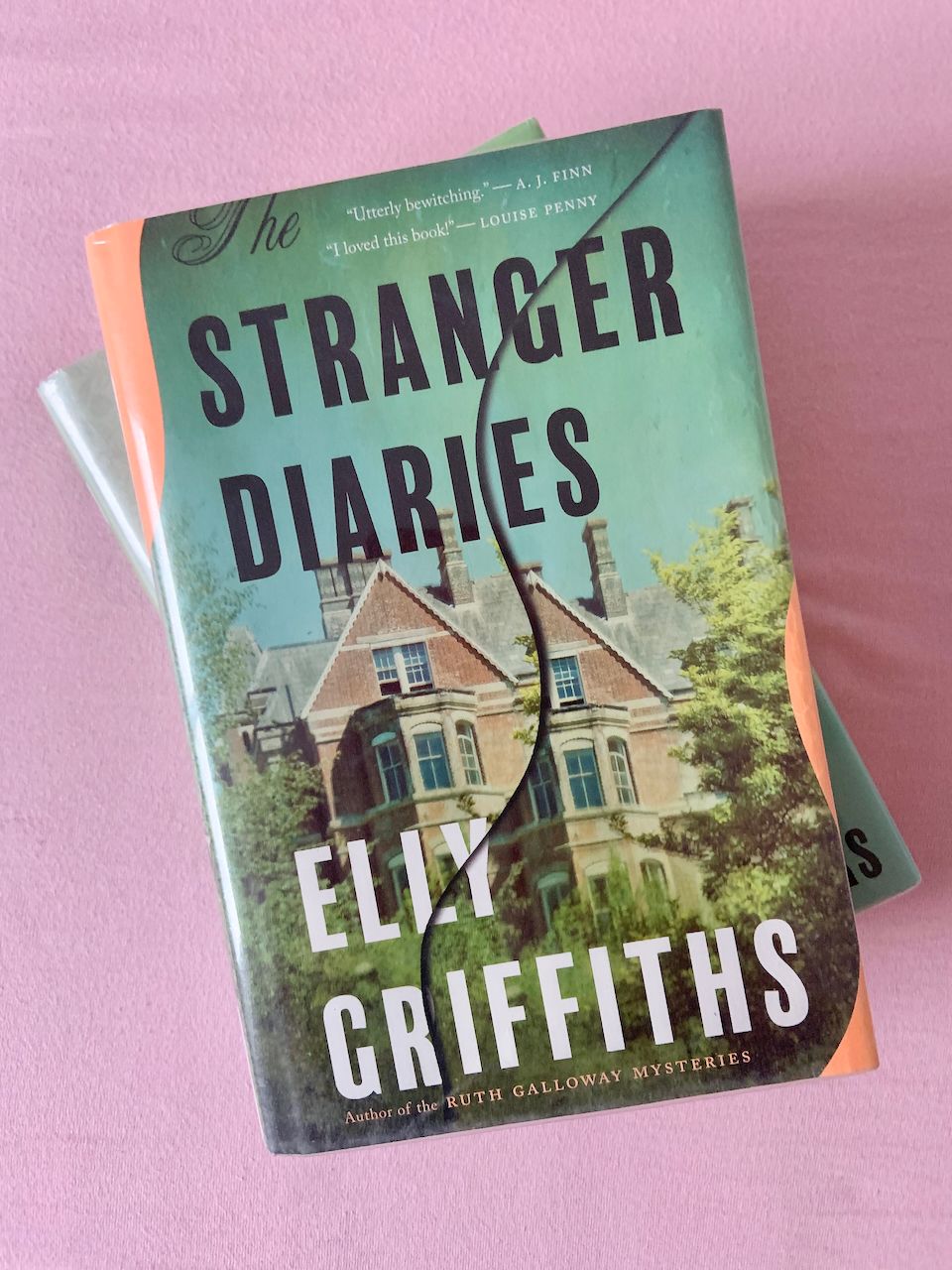

After having devoured The Postscript Murders, I requested for the first book featuring DS Kaur, The Stranger Diaries.

This one was spooky as hell, beginning with a short story and reported hauntings of a school by the ghost of the wife of the author of said story who used to live in the building almost a century ago. It was so different from The Postscript Murders at first that I wasn't even sure the same author had written it.

But then DS Kaur makes an entry about 60 pages into the book and when the story began to be told from her point of view, all felt right with my world. There is sarcasm but not angst, there is humour but not ridicule, and there is diversity and representation done simply splendidly.

'Murder consultant?' says Neil. 'What does that even mean?'

Harbinder counts to five. Her new tactic with Neil is to imagine him as a woodland creature, sly, slightly stupid but ultimately loveable.

'I don't know,' she says, 'but I'd like to find out.'

'Why?' Nibble, nibble, washes whiskers.

'A woman is dead and it turns out she's a murder consultant. Aren't you even the slightest bit curious?'

'The police don't pay us to be curious.' Examines nut, twitches tail.

'They don't pay us much at all.'

~ The Postscript Murders by Elly Griffiths

Griffiths labels these two novels featuring DS Kaur as standalones on her website, and I do hope there are many more to come.

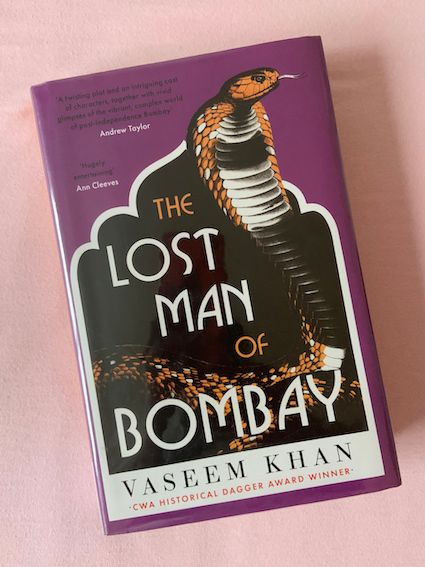

I was quite morose after I finished reading The Stranger Diaries, so I promptly picked up The Lost Man of Bombay by Vaseem Khan, this one being a historical mystery set in 1950s India and featuring India's first policewoman, Inspector Persis Wadia. It's also the third book in the Malabar House series.

I had read the second book, The Dying Day, several months ago and enjoyed it, so I tore through this one during a single sleepless night.

There's much to be enjoyed in Khan's exploration of 1950s Bombay, the post-independence era fraught with a lot of confusion and growth for India.

Wadia is caught in the midst of an existential angst. Most of her male colleagues outrightly disrespect her. Her love interest is an Englishman and a coworker, so that aspect of her life too is riddled with angst. She has been mother-less since she was seven, and her relationship with her father seems to comprise brief exchanges of barbs and stony silences in equal measure. And not to mention the backdrop of a newly free India, which provides the perfect hotbed for a lot of crime and racism and old grudges to surface.

It's a difficult period, and even though I loved reading the familiar names of streets and places which have long been renamed (I grew up at a time when Bombay had not yet become Mumbai, when Victoria Terminus (VT) had not yet been changed to Chattrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST), and apparently it has since been further renamed to Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (CSMT) and so on), it evoked in me a deep, disturbing nostalgia for a place that's long gone, thanks to Khan's masterful descriptions.

As in The Dying Day, there are codes and ciphers to be cracked in this novel too, and the snake on the front cover makes an unexpected and perfectly satisfactory appearance towards the latter half of the book.

I've been reading mysteries for a long time now – who among us hasn't? – and for me it's no longer so much about trying to solve the case before the author does but getting deeply immersed in the characters of the people involved, the criminal and the victims, the inevitable foibles that come with being human.

And having spent a long time away from home, give me a protagonist of Indian origin/background or a book set in 50s-90s India and I'll be drawn to it like a moth to a flame, no questions asked.

Which is why I loved reading the works of both Khan and Griffiths, and I can't wait to explore more of their other books.

A few months ago, I chanced upon an anthology of crime stories, The Perfect Crime: 22 Crime Stories from Diverse Cultures Around the World, edited by Vaseem Khan and Maxim Jakubowski.

In the introduction, both the editors talk about how crime and mystery writing had been essentially 'white' until a couple of decades ago and how this has been rapidly changing with many new, diverse voices from all corners of the world.

Khan's words, as a non-white writer trying to establish his place in a genre that had until recently been dominated by white writers and readers, resonated a lot with me.

Diversity in the publishing industry holds a very personal meaning for me. I wrote my first novel aged seventeen. Over the next twenty-odd years I wrote six more novels, collecting enough rejections to wallpaper a house, until finally receiving a four-book deal for my first crime series set in India.

The interesting thing about that long journey is that only one of those novels featured any non-white protagonists. As an avid reader, I had taken on board the idea that books of the type I was trying to write – genre fiction/commercial fiction – simply didn't feature non-white characters. In my mind I could only hope to be published by writing white characters because those were the sorts of characters readers wanted to read about.

... fiction – especially crime fiction – provides a lens onto society. Literature is a powerful means by which we can change that society for the better. As individuals, we often formulate our views about the world through artistic media. Thus, when we underrepresent minority backgrounds in our artistic output, we run the risk of aiding divisiveness rather than helping to correct it.

The industry makes assumptions about audiences. One prominent assumption is that white readers won't relate to stories about non-white characters.

... Yet some stories need to be told from certain cultural perspectives and won't make sense if you shoehorned in a diverse cast of characters for the sake of political correctness. But the fact is that an industry based purely on human imagination does itself no favours by setting limits on that imagination.

The world is changing. A new generation of readers are emerging who are attuned to diversity, who live in a globalized, interconnected world. Similarly, many traditional readers, for want of a better phrase, are increasingly willing to take risks.

... Readers have an increasingly important part to play in this. The industry responds to readers' buying choices. If readers are willing to take a chance on books featuring diverse characters, the industry will take heed.

~ Vaseem Khan, introduction to The Perfect Crime

Before I published my first book, I toyed with the idea of using a pseudonym that would suggest a white female author.

Apparently, Ashwin Sanghi wrote his first book under a pen name, Shawn Higgins, that was an anagram of his original name.

Taking a cue from that, I jumbled up 'Anitha Krishnan' to come up with 'Kristian Hannah' or 'Kristina Hannah', but that was too close to the name of a best-selling author Kristin Hannah, whose books I love!

Eventually, I decided to go with my own name Anitha Krishnan, adopting the attitude that if someone didn't want to purchase my books because of my name, then that's their problem, not mine.

When I started writing Dying Wishes, a lot of Indian mythology began to seep into it involuntarily, much to my dismay, because as Khan says about crime, fantasy too has largely been a white-dominated genre and besides, who'd care to read about Hindu culture, that too South Indian culture which is so not Bollywood, written by an unknown author?

Eventually, using any name other than my own, even resorting to initials to hide my gender, felt tantamount to trickery to me. And so I stuck with Anitha Krishnan.

I won't say I was glad about it right away, but in hindsight I am mighty glad about the path I chose to take and also about writing tales that have sprung from my background, which although very global in outlook is also unabashedly and unapologetically Indian in origin.

What I can give to the world is myself. And I can't do that if I keep trying to be someone else or rejecting myself in any way whatsover.

So here's to more diversity and inclusion. When we all are free to be who we are, the real world becomes the kind of place that we seek in fiction: kinder, more compassionate, and encouraging.